DRY ME A RIVER: JavaScript Loops, Functions, Scope, Frequency Counters and Closures

Title: DRY ME A RIVER: JavaScript Loops, Functions, Scope, Frequency Counters and Closures

Type: Lesson

Duration: 8hrs

Creator: Arthur Bernier Jr

Topics: JavaScript Loops, Functions, Scope, Frequency Counters and Closure: A Lesson

By the end of this lesson, learners should be able to:

- Understand the purpose and usage of loops in JavaScript, including for, while, and do...while loops in DRY Code.

- Define and invoke JavaScript functions, passing arguments and returning values as needed.

- Differentiate between global and local scope in JavaScript, and explain the visibility and lifetime of variables.

- Explain the concept of closure in JavaScript and demonstrate its usage in practical examples.

- Apply the concepts of loops, functions, scope, and closure together in a real-life example, such as calculating the total cost of items with a discount.

- Apply the Frequency Counter Pattern

- Understand the JavaScript Call Stack and JavaScript reads our code.

What is DRY?

The DRY principle is what I like to call being ambitiously lazy. It's all about doing something really good one time, so you don't need to redo it over and over again repeating all the same steps.

Loops and especially functions help us do this, and also beleive it or not Closure and Frequency Counters do this also.

DRY stands for "Don't Repeat Yourself" and encourages developers to write code that does not repeat itself.

By not repeating yourself, you are making your code easier to read, debug, maintain, and extend. This helps you save time by avoiding the need to make multiple changes in the same place if something needs to be changed.

When writing code, always keep the DRY principle in mind so that your code is as efficient as possible!

JavaScript Loops, Functions, Scope, and Closure

- Loops: Loops allow you to execute a block of code repeatedly until a certain condition is met. There are various types of loops in JavaScript, such as for, while, and do...while loops.

- Functions: Functions are reusable blocks of code that can be defined and invoked by a specific name. Functions can accept arguments and return values. They help to organize and modularize your code, making it more readable and maintainable.

- Scope: Scope determines the visibility and lifetime of variables in your code. JavaScript has two types of scope: global and local. Global variables are accessible from anywhere in your code, whereas local variables are only accessible within the function they are declared in.

- Frequncy Counters: Frequency counters are a common problem-solving pattern used in programming, especially when it comes to comparing different data sets. This pattern involves creating an object or array that stores the frequency of each element, allowing you to easily compare and manipulate the data.

- Closure: Closure is a feature in JavaScript that allows a function to remember and access its outer (enclosing) scope's variables, even after the outer function has finished executing. Closures enable a more functional programming style and are used in many advanced JavaScript patterns.

Explanation

Loops

- For loop

A for loop is used when you know how many times you want to iterate through a block of code. It consists of an initialization, a condition, and an increment/decrement.

for (let i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

console.log(`Iteration ${i}`);

}In this example, the loop will iterate five times, with the variable i incrementing from 0 to 4.

- While Loop

A while loop is used when you want to iterate through a block of code as long as a specific condition is true. It checks the condition before each iteration.

let i = 0;

while (i < 5) {

console.log(`Iteration ${i}`);

i++;

}In this example, the loop will iterate five times, just like the for loop example, as long as i is less than 5.

- Do...While Loop

A do...while loop is similar to a while loop but it checks the condition after each iteration, which means the code block will always execute at least once.

let i = 0;

do {

console.log(`Iteration ${i}`);

i++;

} while (i < 5);In this example, the loop will iterate five times, just like the for and while loop examples, as long as i is less than 5.

Functions

Why Should I care about this I just want to know REACT

- JavaScript Functions are incredibly versatile and in javascript they are what's known as first class citizens meaning they can be passed around like any other object.

- Functions are literally objects in JS the same way Arrays are as you learned before.

- We will be using Functions everyday in JavaScript so you will learn more and more about them daily through repitition.

Setup

make a file functions.js or create a repl in repl.it

Test that a console.log will appear in Terminal when you run the file if you don't use repl.it.

$ node functions.jsWhat is a function?

// 2 ways of creating functions

// function declaration

function one () {

return 'one'

}

one()

// function expression

const two = () => {

return 2

}

const shotenedTwo = () => 2Describe why we use functions

Using functions is another application of DRY. Don't Repeat Yourself. With a function, you can store code that can be used conveniently as many times as you wish, without having to rewrite the code each time.

Demonstration

Defining a function

const printBoo = () => {

console.log('======');

console.log('Boo!');

console.log('======');

};Always use const to declare your functions. It would be a strange day when a function would need to be reassigned.

The code will not run yet. The function needs to be invoked.

Invoke a function

Use one line of code to run multiple lines of code

printBoo();Simply use the name of the variable and use parentheses to invoke the function.

If the parentheses are not included, the function will not run.

The invocation comes after the function definition. If you write it beforehand, it will be trying to invoke something that doesn't yet exist according to the interpreter.

This will work:

const printBoo = () => {

console.log('======');

console.log('Boo!');

console.log('======');

};

printBoo();VS

This will not:

printBoo();

const printBoo = () => {

console.log('======');

console.log('Boo!');

console.log('======');

};Note: There is a special case called hoisting but we won't cover that behavior today, but we will in this class.

Imitation

Code Along

- Write a function

printSumthat will console.log the result of 10 + 10

Extra Reps

-

Write a function

printTrianglethat will print these pound signs to the console (there are 5 console.logs inside the function):# ## ### #### ##### - Make it so that

printTrianglewill print the pound signs using a for loop (there is a for loop and only 1 console.log inside the function). - Make it so that when you can invoke the function with the number of pound signs to print (not just hardcoded to print 5)

Properly name a function

The variable you use for a function should contain a verb. Functions do something, most often:

- getting data

- setting data

- checking data

- printing data

If the purpose of your function is to check data, for example, use the verb check in the variable name.

Example function that contains a conditional:

const checkInputLength = (input) => {

if (input.length > 10) {

console.log('input length is greater than 10');

} else {

console.log('input length is not greater than 10');

}

};- A Function name should always start with a verb

- A function if possible should be pure meaning it shouldn't effect anything outside of itself

- If it does effect something outside of itself you should let the resder of the function know that by the name for example we could have a function that checks if something is or isn't something

- we could also have a function that changes something or Mutates something like when you are playing a video game and you score a point, the function that updates the score could be called updateScore or setScore or changeScore

- Functions should try to do only one thing If a function, called

checkInputLength, does more than just check input, then it is a poor function.

// function that mutates

const ricMershon = {

age: 21

}

const scottDraper = {

age: 25

}

const increaseAge = (person) => {

person.age += 1

console.log (`Horray it's your ${person.age} birthday`)

}

Takeaway: Think about appropriate verbs to use in your function variable names. The verbs should indicate the one thing that the function does.

Write an arrow function with a parameter

The preceding function, checkInputLength had a parameter called input.

Functions can receive input that modify their behavior a bit. This input is called a parameter.

In the below example, the parameter is arbitrarily called name. We can call our parameters whatever we want - whatever makes semantic sense.

Using concatenation I can put the input into a string:

const sayName = (name) => {

console.log('Hello! My name is ' + name);

}When we invoke the function, we can specify the value of the parameter, this is called an argument:

sayName("Frodo");We can continue to invoke the function with whatever arguments we want:

sayName("Merry");

sayName("Pippin");

sayName("Sam");Each time, the output of the function will change to reflect the argument.

Argument vs Parameter

The argument is the input, the parameter is how the input is represented in the function.

const func = (PARAMETER) => {

// some code

}

func(ARGUMENT);Write an arrow function with multiple parameters

A function can take any number of parameters.

const calculateArea = (num1, num2) => {

console.log(num1 * num2);

}When you invoke the function, you generally want to supply the right number of arguments.

calculateArea(4, 4)=> 16

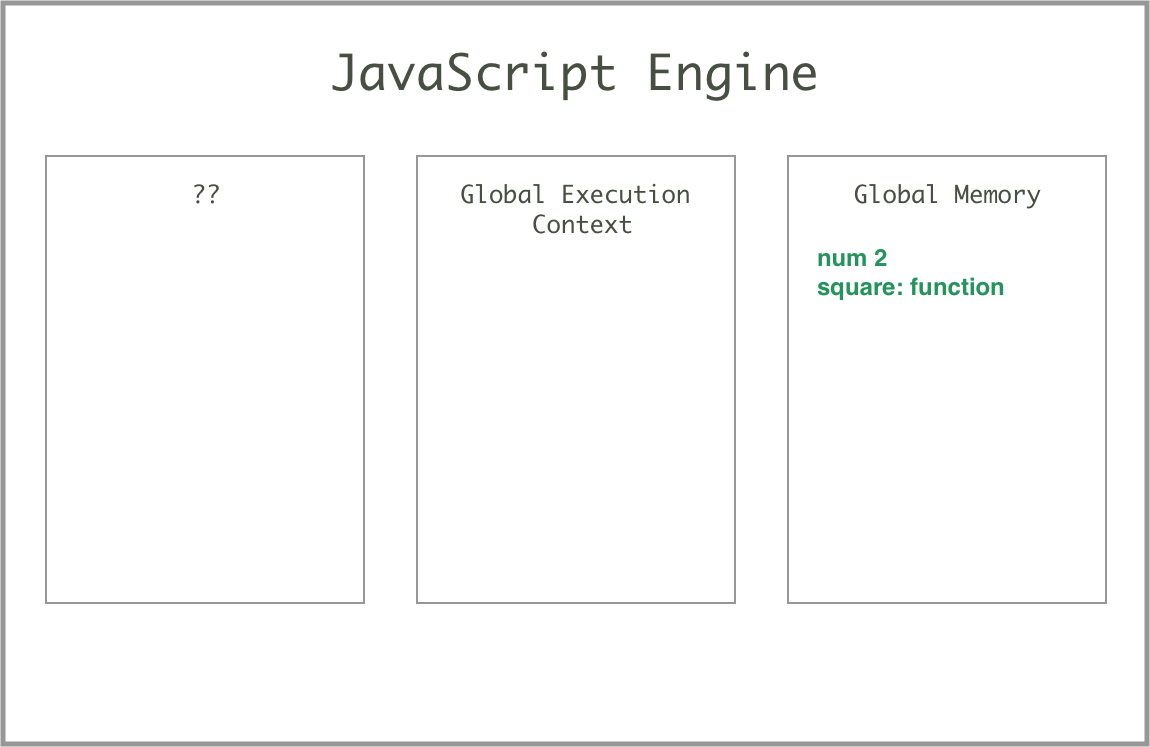

How does this work? Aka (The Execution Context Interview Question Answer)

let num = 2;

const square = (x) => {

return x * x

}so in our code we have now created a variable num on line 1 that is equal to 2 and then created a variable called sqaure that is equal to the function we created.

JavaScript does 3 super awesome things that makes it a great very first programming language, and that makes it elegant enough to be used by developers with decades of experience.

We will go over those things as we go through this course but what pertains to us is the awesome feature of the JavaScript being single threaded and reading code line by line and executing code only when you ask it to.

So in JS when it comes to what's running in our code we are never too confused if we remember JS goes line by line and 1 at a time.

And we keep track of this in what's called our Execution Context

So when the JS Engine looks at our code it will start at the top and perform each operation line by line

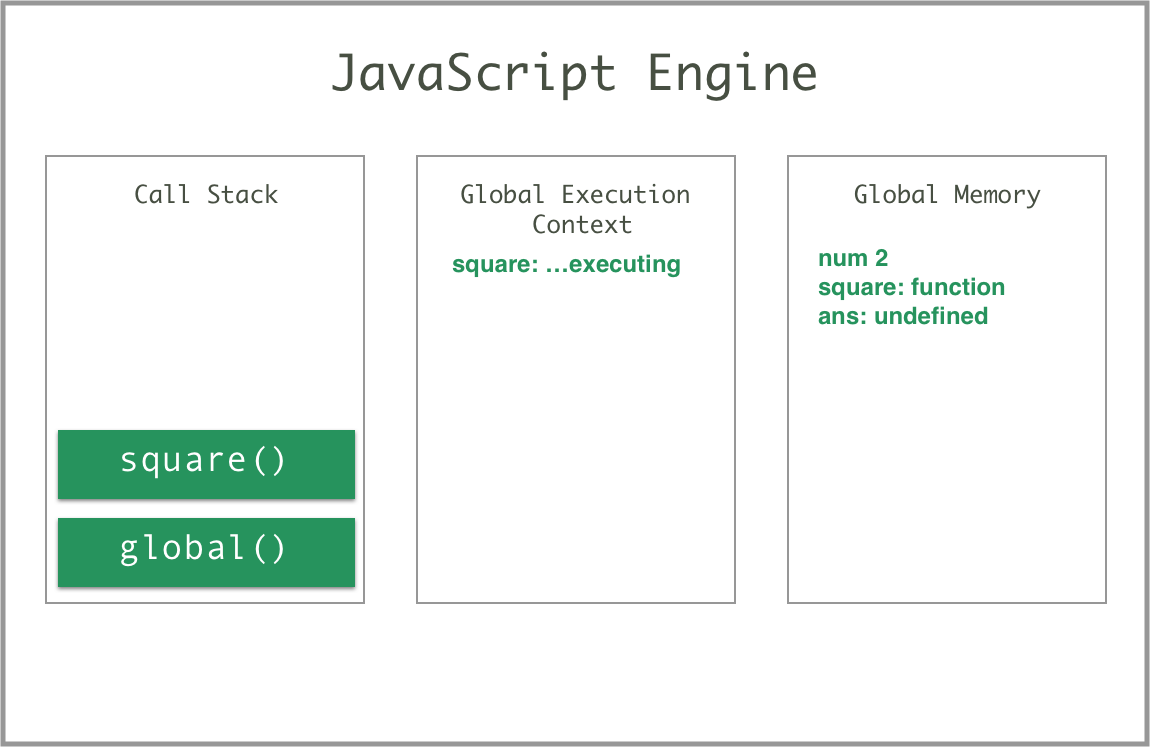

let num = 2;

const square = (x) => {

return x * x

}

const ans = square(num)So as you can see when we call a function we go ahead and add it to the stack of things that we want JS to do. Once JS has finished that task it goes back to the main code on the next line and runs again.

So once square has completed running it will give us a value and assign it to ans

let num = 2;

const square = (x) => {

return x * x

}

const ans = square(num)

console.log("Hello World")what order will this happen

let num = 2;

const square = (x) => {

return x * x

}

console.log("Hello World")

const ans = square(num)what about this?

Scope

Scope refers to the visibility of variables in your code. There are two types of scope in JavaScript: global scope and local scope.

A variable declared outside a function or a code block has a global scope, meaning it can be accessed from anywhere in your code. On the other hand, a variable declared inside a function or a code block has a local scope, meaning it can only be accessed within that function or block.

Example 1: Global vs. Local Scope

var globalVar = "I am global!";

function exampleFunction() {

var localVar = "I am local!";

console.log(globalVar); // Accessible: "I am global!"

console.log(localVar); // Accessible: "I am local!"

}

exampleFunction();

console.log(globalVar); // Accessible: "I am global!"

console.log(localVar); // Error: localVar is not definedIn this example, globalVar has a global scope and is accessible both inside and outside the exampleFunction. localVar, however, has a local scope and is only accessible within exampleFunction.

Example 2: const, let, and var in Block Scope

if (true) {

var varVariable = "I am var!";

let letVariable = "I am let!";

const constVariable = "I am const!";

}

console.log(varVariable); // Accessible: "I am var!"

console.log(letVariable); // Error: letVariable is not defined

console.log(constVariable); // Error: constVariable is not definedIn this example, we can see the difference between var, let, and const within a block. var does not have block scope and is accessible outside the block, while let and const have block scope and are not accessible outside the block.

Closure

A closure is a function that has access to its own scope, the scope of the outer function, and the global scope. In other words, a closure can remember and access variables and arguments even after the outer function has finished executing.

Example 1: Basic Closure

function outerFunction() {

const outerVar = "I am from outer function!";

function innerFunction() {

console.log(outerVar);

}

return innerFunction;

}

const closure = outerFunction();

closure(); // Output: "I am from outer function!"In this example, outerFunction returns innerFunction, and we assign the returned value to the variable closure.

When we call closure(), it's able to access and print outerVar even though outerFunction has already finished executing.

Example 2: Closure with Function Arguments

function greetingGenerator(greeting) {

return function (name) {

console.log(`${greeting}, ${name}!`);

};

}

const helloGreeting = greetingGenerator("Hello");

const hiGreeting = greetingGenerator("Hi");

helloGreeting("John"); // Output: "Hello, John!"

hiGreeting("Jane"); // Output: "Hi, Jane!"In this example, greetingGenerator returns a function that takes a name argument. The returned function has access to the greeting argument of the outer function. When we create helloGreeting and hiGreeting and call them with different names, they remember and use the greeting values they were created with.

Real-life Example: Read Line By Line

Imagine you are building a web application that displays a list of items with their prices and calculates the total cost after applying a discount.

function calculateTotal(items, discountRate) {

let total = 0;

function applyDiscount(price) {

return price - (price * discountRate);

}

for (let i = 0; i < items.length; i++) {

const discountedPrice = applyDiscount(items[i].price);

total += discountedPrice;

}

return total;

}

const items = [

{ name: 'Item 1', price: 100 },

{ name: 'Item 2', price: 200 },

{ name: 'Item 3', price: 300 },

];

const discountRate = 0.1;

const totalPrice = calculateTotal(items, discountRate);

console.log(totalPrice);In this example, we use a for loop to iterate over the items array. We define a calculateTotal function that accepts items and a discount rate as arguments. Inside the function, we declare a local variable total and an inner function applyDiscount.

Advanced Real-world Example: Debounce Function

A debounce function is a higher-order function that can be used to delay the execution of a function until after a specified time has passed since the last time it was called. This can be particularly useful for optimizing performance in events that fire frequently, such as window scrolling or resizing, and user input events like typing in a search box.

Closures play a crucial role in implementing debounce functions, as they allow us to maintain a reference to the original function and its arguments, as well as any internal state needed for managing the debounce behavior.

Here's an example of a simple debounce function:

function debounce(func, wait) {

let timeout;

return function () {

const context = this;

const args = arguments;

clearTimeout(timeout);

timeout = setTimeout(function () {

func.apply(context, args);

}, wait);

};

}

// Usage:

function logUserInput() {

console.log("User input detected");

}

const debouncedLogUserInput = debounce(logUserInput, 300);

document.getElementById("searchBox").addEventListener("input", debouncedLogUserInput);In this example, the debounce function takes a func and a wait time as its arguments. It returns a new function that, when called, will clear any existing timeout and set a new one to call the original function after the specified wait time has passed. The closure allows the returned function to maintain access to the func, wait, timeout, context, and args variables even after the debounce function has finished executing.

When we use the debouncedLogUserInput function as an event listener for the input event of a search box, the logUserInput function will only be called once the user has stopped typing for at least 300 milliseconds. This prevents the function from being called too frequently and potentially causing performance issues.

Frequency Counters

Frequency counters are a common problem-solving pattern used in programming, especially when it comes to comparing different data sets. This pattern involves creating an object or array that stores the frequency of each element, allowing you to easily compare and manipulate the data.

Example Problem

Suppose you are given two arrays, arr1 and arr2. You need to determine if each value in arr1 has its square in arr2, and the frequency of the values should be the same. For example, given the arrays [1, 2, 3] and [1, 4, 9], the function should return true, but for [1, 2, 1] and [1, 4, 4], it should return false.

Step 1: Create the frequency counter function

Create a function that takes two arrays as input and returns a boolean value indicating if the arrays match the conditions.

function frequencyCounter(arr1, arr2) {

if (arr1.length !== arr2.length) {

return false;

}

// Create frequency counters

const counter1 = {};

const counter2 = {};

// ... (next steps)

}Step 2: Count the frequencies of elements

Iterate through both arrays, incrementing the count for each element in their respective frequency counters.

for (let val of arr1) {

counter1[val] = (counter1[val] || 0) + 1;

}

for (let val of arr2) {

counter2[val] = (counter2[val] || 0) + 1;

}Step 3: Compare the frequencies

Now, iterate through the first counter, checking if each value has its square in the second counter and if the frequencies match.

for (let key in counter1) {

if (!(key ** 2 in counter2)) {

return false;

}

if (counter2[key ** 2] !== counter1[key]) {

return false;

}

}Step 4: Return the result

If the function has not returned false yet, it means the arrays satisfy the conditions, and we can return true.

return true;Now you have a simple frequency counter function that can compare two arrays based on the given conditions. This pattern is helpful for solving various problems efficiently, especially those related to data comparison and manipulation.